Dinah, ClinkShrink, & Roy produce Shrink Rap: a blog by Psychiatrists for Psychiatrists, interested bystanders are also welcome. A place to talk; no one has to listen.

Saturday, September 30, 2006

FDA Drugs: Sept 2006

Just a quick list of relevant FDA and related notices...

Lamictal & Pregnancy: cleft lip in first trimester... see also Neurology abstract reviewing risk of fetal abnormalities in 4 anticonvulsants (note: take numbers with grain of salt... the N for each drug exposure is kinda low)

Generic Topamax released

Effexor label revised: mentions risk of serotonin syndrome with triptans

Abilify 7.5mg injectable: approved for agitation associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

Contrave advances: New obesity drug... combines Wellbutin/bupropion and Revia/naltrexone to cause weight loss... 6-month trial in 250 people results in 7.5% wt loss (vs 1% for placebo). [see also Orexigen site]

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Sister Fortune

Every day on the way to work I pass an interesting little business. The front window has a couple neon lights that spell out 'Tarot Cards' and 'ESP'. The sign by the highway reads "Sister Liz: Psychic Readings and Advisor". The interesting thing about this is that there are always one or two cars parked out front. Whenever I see this I wonder how many of Sister Liz's clients are also seeing a psychiatrist---or not seeing the psychiatrist they need---and what other alternative treatments they are using. For the most part I don't think a consultation with Sister Liz would do any particular harm other than thinning one's pocketbook. Who am I to complain about a gypsy fortune teller? There are scads of healing paradigms to choose from: chiropractic, aromatherapy, accupuncture, Chinese herbalism, "root" workers, sweat lodge, exorcism, ayurvedic medicine, meridian therapy and even angel adjustment. People talk about rising health care costs, but alternative treatments can be fairly pricey too. Regardless, I think that if they're paying out-of-pocket it's up to them what kind of consultant they see.

Every day on the way to work I pass an interesting little business. The front window has a couple neon lights that spell out 'Tarot Cards' and 'ESP'. The sign by the highway reads "Sister Liz: Psychic Readings and Advisor". The interesting thing about this is that there are always one or two cars parked out front. Whenever I see this I wonder how many of Sister Liz's clients are also seeing a psychiatrist---or not seeing the psychiatrist they need---and what other alternative treatments they are using. For the most part I don't think a consultation with Sister Liz would do any particular harm other than thinning one's pocketbook. Who am I to complain about a gypsy fortune teller? There are scads of healing paradigms to choose from: chiropractic, aromatherapy, accupuncture, Chinese herbalism, "root" workers, sweat lodge, exorcism, ayurvedic medicine, meridian therapy and even angel adjustment. People talk about rising health care costs, but alternative treatments can be fairly pricey too. Regardless, I think that if they're paying out-of-pocket it's up to them what kind of consultant they see.My main bone of contention is the use of the term 'complementary' medicine. According to Dictionary.com (my favorite source of all things lexicographal) the term 'complementary' means supplying mutual needs or something that completes the whole. The implication is that complements, when combined, offset one another or blend to create a unified whole. Nice idea, but total...uh...horse hooey when it comes to medicine. Aromatherapy has as much relevance to traditional medicine as tanks have to gardening. The National Institute of Health has a branch dedicated to studying alternative and complementary therapies of many kinds but it seems to me that the number of proposed therapeutic modalities are growing faster than they can possibly be validated. And as far as I've seen they're not funding any clinical studies on the effects of fortune tellers or exorcists.

Separate from efficacy issues---or lack thereof---there's the question of potential harm. In one study done in Boston, a random sampling of ayurvedic medicines sold in the Boston area revealed that 20% of these compounds were contaminated with heavy metals such as arsenic and lead. There are over a thousand publications in PubMed related to herbal remedies alone; many of these are case reports of serious complications from these interventions.

I'm sure there are many reasons why people don't pursue traditional medicine---lack of finances, fear and trust issues or cultural affiliation---but this does not lessen our obligation to ensure safety and efficacy. And that can't be done by looking in a crystal ball.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

For She's A Jolly Good Fellow

I love working with students. Maybe I'm showing my age, but every year they show up younger and younger, bright and energetic, wide-eyed with enthusiasm.

I love working with students. Maybe I'm showing my age, but every year they show up younger and younger, bright and energetic, wide-eyed with enthusiasm.And I get to take them to prison. They seem so innocent I thought about calling this post "Bambi Goes To Jail" but that just seemed wrong.

My students want to work with criminals. They have signed up for a full year of experience evaluating and treating people with mental illnesses involved in tthe criminal justice system. At least six months of that training is required to take place inside a correctional facility.

They are already used to working in hospitals with severely mentally ill folks. They have also already worked with people involved in the criminal justice system while working on those inpatient units; they may or may not have been aware of it, but chances are good that a certain percentage of their inpatients had open charges or were on parole or probation. So then the only thing they really haven't had experience with is the correctional environment itself.

I make sure they have a good experience. The facility we work in is relatively new---well OK, younger than I am at least (don't touch that Dinah, I know where Max lives!) so that means it's new from a building standpoint. It has security bells and air conditioning and modern ventilation and (usually) working elevators. My students get an office of their very own with a real desk, chair and working telephone. They are not seeing patients in a linen closet. I am with them throughout their clinic and am readily available to answer questions or solve problems. I let them run their own show within the limits of the system, and I give them feedback about what to expect from the system. If all goes well, by the end of the rotation I have them at least somewhat considering a career in corrections. Even if they don't work corrections at the very least they've got a good idea how free society facilities interact with my system for patient transfers and other issues. They have a more complete view of the institutional public mental health system by the time they're done.

So it's a good thing. I wish I could get more of them to stay but I realize it's not for everyone. My aim is mainly to be a good Bambi mama.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Please Understand

If you read Richard Friedman's article Empathy and Understanding Aren't Enough in today's New York Times, you said to yourself, "Shrink Rap's gonna be all over this one."

Dr. Friedman writes:

I could already sense trouble. After six years of insight-oriented therapy, this patient had little sense of his own role in his unhappiness or what to do to turn his life around.

Next, I tried something a little more challenging: “I don’t get a sense from what you’ve told me that you feel responsible yourself to do anything to improve your life.”

With this, he sat bolt upright in the chair, crossed his arms and replied icily: “I’ve been working very hard all these years in therapy. You have no right to say that. You hardly know me.”

He had been working very hard all right — to maintain his status as a victim of a troubled history. And this was something he was loath to surrender. He clung to the notion that he was unhappy because he had been mistreated by various figures in his life: his parents, his teachers and disloyal friends, among others.

Dr. Friedman goes on to tell us that he helped this patient by telling him to grow up and get a job.

So I treat this patient as well as a few of his clones. The problem of being a victim and using this status to justify dysfunction is not uncommon, though I would argue with Dr. Friedman that it's hard not to sympathize with someone who has had a miserable childhood. Why some people move on and others stay stuck is as perplexing as why some folks have one reaction to a medication and others don't.

In past posts, I've made the comment that psychotherapy is a safe place for a patient to hear difficult things. So, I like the premise of Dr. Friedman's article though it's never been my experience that psychotherapy is simply about validating suffering and colluding with dysfunction; only a lousy therapist would do this. The role of empathy and understanding, however, is in itself often comforting and healing, and at the minimum, it supports the therapeutic alliance. The part I find hard to buy is that so soon (?the first session), Dr. Friedman took a patient who didn't particularly like him and yet was so quickly able to fix him without the backdrop of empathy.

No one listens to me like this.

Liar! Liar!

Well, it's finally happened. This morning I officially discontinued treatment on more inmates than I provided treatment for during my morning clinic. Policy dictates that if you don't show up to take your medicine for three days in a row, it gets stopped. If an inmate signs a refusal form, treatment gets stopped.

I'm still trying to figure this out. These guys come in from court complaining about how prison "isn't going to help me." They get screened for medical and mental disorders at the front door. They get enrolled in chronic care clinics for medical and mental disorders. They're provided treatment and all of this is done automatically, without having to ask for it, totally for free.

And then they drop out of treatment.

All they have to do is go to the pharmacy window to pick up their medicines. All they have to do is keep their appointments. All they have to do is show up. Treatment requires almost no responsibility on their part.

And they drop out of treatment.

I suppose I should be more sympathetic. I know that a decision to accept or reject treatment in a correctional facility is a complicated one. Accepting treatment means taking the risk that someone else may find out you're 'crazy'. It means potentially being turned down for institutional jobs or other programs because you take medication. It means having to admit that you really do have a disease that you'll have to deal with for the rest of your life. It means dealing with the frustration of coming down for Pill Line every day. And it's not like my patients are known for their good judgement.

But before I even start treatment I talk to these guys about all this. I ask them if they're willing to do it, and they promise me they are. Then they stop taking their medicines a week later. I wish I had some way of knowing who was being sincere or not because then I would be able to focus my resources on the ones who truly want help. If they said to my face that treatment was a waste of time and they didn't want it, I'd respect that decision. I'd remind them of the consequences of noncompliance and how to get back into treatment when the time comes, but I'd respect the decision.

So some of my patients lie to me about their compliance. Liars? In prison? Shocked! I'm shocked, I tell you.

I just wish it didn't require so much paperwork.

Sunday, September 24, 2006

A Taste of Our Own Medicine?

I'm prone to rumination and a number of years ago, a shrink friend (but not a shrink rapper) told me I should take Zoloft. No one before or since has ever suggested I should take a psychotropic medication and I dismissed my friend's suggestion with the thought that it was motivated by something along the line of misery loves company. You see, my friend had an anxiety disorder for which she was taking Zoloft, and she found it helpful; while I don't imagine she told everyone she met to take Zoloft, I did think it predisposed her to see whatever my issue of the moment was as psychopathology, not just any old psychopathology, but pathology just like hers that would be helped by Zoloft, just like hers.

So we worry that our practice of medicine will be influenced if we're given pens by the pharmaceutical companies. If we're talking about how that free lunch influences us, might we talk about how the doctor's personal response to medication effects his practice? It's common for psychiatric residents to discuss whether it's necessary to have a personal psychotherapy in order to become a psychotherapist. No one talks about how their own responses to illness and treatment effect their own practices with regard to diagnosis and treatment.

Docs are human, I imagine that if a doctor finds a medication helpful, or has a horrible reaction to it, his practice will be influenced. If I've had a rare but extreme adverse reaction, how can I possibly order such a treatment without fearing my patient might have the same rare but extreme adverse reaction, even if the odds of the same reaction might be a zillion to one? Don't we all get sensitized by our personal experiences?

Plop plop, fizz fizz?

Saturday, September 23, 2006

In The Family Way

I think there's a rule among correctional switchboard operators that any telephone caller who sounds angry or has a strong foreign accent must immediately be routed to the psychology department. That's the only explanation for some of the calls we get; usually it's a family member calling to demand a reason why their loved one hasn't been transferred to a maintaining facility yet or hasn't had a parole hearing or why he wasn't taken to court on the appointed day. Sometimes they need to yell at someone because of that very unfair sentence that will keep Loved One from paying their bills. Now, keep in mind that the psychology department doesn't have anything to do with any of these issues. The purpose of our involvement mainly is to give the caller someone to vent at, and occasionally to provide a little community education about the prison intake process.

I think there's a rule among correctional switchboard operators that any telephone caller who sounds angry or has a strong foreign accent must immediately be routed to the psychology department. That's the only explanation for some of the calls we get; usually it's a family member calling to demand a reason why their loved one hasn't been transferred to a maintaining facility yet or hasn't had a parole hearing or why he wasn't taken to court on the appointed day. Sometimes they need to yell at someone because of that very unfair sentence that will keep Loved One from paying their bills. Now, keep in mind that the psychology department doesn't have anything to do with any of these issues. The purpose of our involvement mainly is to give the caller someone to vent at, and occasionally to provide a little community education about the prison intake process.Most folks don't usually think about family involvement in correctional healthcare but they definitely do get involved. As a general rule I don't mind talking to family members who call if the inmate says it's OK. It's a good thing for me to have someone on the "outside" helping me keep an eye on my patients. They have more regular contact with my patients than I do and they are fairly good at identifying early symptoms of relapse. Regardless of their reason for calling, at some point in the conversation I make a habit of telling them to keep an eye on Loved One and to call the psychology department if they notice anything of concern. That quickly turns a potentially adversarial relationship into an alliance---and I think it surprises them. They expect to get dismissed or blown off, or they call expecting that any prison doc is going to be a heartless Nazi. And it gives me a chance to emphasize to them that Loved One has been seen and is going to be followed regularly. I tell them to remind Loved One about his next scheduled appointment and to take his medicine.

The sad phone calls are the ones involving first-time inmates. By the time someone ends up in prison they have usually run the gamut of lesser sanctions and failed repeated 'second chances'. Then I hear from the naive current girlfriend or the exhausted mother in their last futile attempt to rescue Loved One from the consequences of his stupidity. I must tactfully suggest that it would be best for them to care for themselves during this time of reprieve and let Loved One fend for himself. It's hard to do that without sounding like a heartless Nazi, but someone has to suggest that it's time for Loved One to grow up. Mostly I think they need someone who can empathize with their frustration and emotional fatigue.

Once in a blue moon I'll get a call from a family member after someone has been released. Those are the phone calls I like because it means my patient has actually decided to stay in treatment---they're calling for prescription refills or referral information, or records for a free society psychiatrist. Those are the patients I don't usually see again. And that's a good thing.

Friday, September 22, 2006

ClinkShrink's Day Off

Oh Yeah....

Oh Yeah....Where to begin, where to begin...

I'm back from a week off blogging. I was absent thanks to my little buddy Harold the Vampire Cat who desperately needed a housesitter & catsitter. Unfortunately, Harold lives out in the boondocks with no Internet access.

And now today I have a day off. After giving a morning lecture I had a leisurely lunch with friends and now I am home mulling my options: shop or nap, shop or nap, shop or nap. Nahhh: time to blog. And nothing serious because my brain just isn't up to it. In situations like this there's only one possible topic:

What got me started thinking about this was the recent story about the skeleton of the 3 million year old girl that (who? when you've been dead for 3 million years do you still count as a 'who'?) was found in Ethiopia. It's almost a complete skeleton, the best one ever found, and scientists are hopeful that it will tell us a lot about early child hominids. I found myself wondering what 3 million year old 3 year old girls play with. I wondered if she had a support duck. Then I remembered reading this story about the ancient precursor to modern waterfowl: the so-called Demon Duck of Doom. It had powerful jaws and was thought to be a meat-eater. Probably not much of a support to ancient little girls.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

SSRI Antidepressants & Violence

There's an article over at PLoS Medicine about antidepressants that makes for interesting reading. The article, Antidepressants and Violence: Problems at the Interface of Medicine and Law by David Healy, Andrew Herxheimer, & David B. Menkes, reviews pharmaceutical company data regarding SSRI-induced violence, aggression, and hostility. The main antidepressant reviewed is paroxetine (Paxil, Seroxat, others), though fluoxetine/Prozac, sertraline/Zoloft, and venlafaxine/Effexor XR, are mentioned.

The three authors acknowledge that they have all served as expert witnesses supporting and opposing the role of SSRI antidepressants, which makes the article seem a bit like an advertisement for their expert witness business. Nonetheless, the review of drug company data (mostly GSK) is worth a gander.

Roy: I found most interesting the low incidence of episodes of "hostility" among both those on drug or placebo. For example there were only 55 (0.4%) reports of "aggression" or "assault" in 13,741 adverse effect monitoring reports from the UK of paroxetine, and 1 report of "murder". I'll leave it to the reader to find incidence reports in the general population, but I'm guessing it is at least this or higher.

GlaxoSmithKline's data from all of their placebo-controlled paroxetine trials showed "hostility events" (which includes mere thoughts as well as actions) in a total of 60 out 9219 paroxetine cases (0.65%) and 20 out of 6455 placebo cases (0.31%). Statistically, one appears to be twice as likely to have an "hostility event" on Paxil than on placebo.

The lawyers are lining up at the courthouse for business (Clink, feel free to pick up on that one).

The article, which anyone can view in its entirety (that's what I like about PLoS Journals), includes 9 actual case examples or folks who did bad things, like robbery and murder, after taking SSRIs (sometimes after only 2 doses).

Clink:

There's a reason why this article was not published in a standard peer-reviewed journal. It seems like an article that can't make up it's mind about what to discuss. It didn't really address the legal issues involved in drug-related criminal prosecution and it's an incomplete discussion of the clinical studies. Frankly, I left the article feeling a little bothered by the lack of focus.

Regarding the clinical issues: violence is a multifactorial behavior, and I think it's overly simplistic to reduce it to a simple medication cause-and-effect. Confounding variables are the presence of personality disorders, previous acts of violence, active affective disorder symptoms and co-existing substance abuse. We know nothing about these confounding variables from this article. While clinical trial data will be useful to identify strong associations that could be attributed to medications (eg. weight gain, increases in prolactin levels) it is less useful for low base-rate phenomena like homicide. As Roy has already pointed out, base rates of general aggression were low to begin with in the clinical monitoring data from the UK.

Regarding the legal issues: that was actually the interesting part for me, and they totally glossed over it! They only presented their own small case series. They didn't discuss diminished capacity defenses, insanity or involuntary intoxication. To keep it simple (and to minimize the length of this post) I'm only going to talk about involuntary intoxication.

When it comes to mental health defenses in crime, all jurisdictions exclude voluntary intoxication as a defense. This is done for the obvious reason that the majority of violent offenses occur under the influence of drugs and alcohol, so social policy dictates that people must be held accountable for the consequences of their choice to abuse substances. However, longterm use of some substances can cause permanent mental changes long after the person is abstinent. PCP psychosis can persist for months after chronic abusers stop using. Longterm alcohol dependence can result in permanent memory deficits. These residuals problems can be used as the basis for a legal defense.

Another legal theory that allows for substance abuse is the idea of involuntary intoxication---what I think of as the "mickey" defense---meaning that you took something without knowing it. Drinking spiked punch or accidentally taking the wrong pill might be an involuntary intoxication. Having an unusual or rare reaction to a medication---like an SSRI---could be a type of involuntary intoxication defense. Something like this would be more common with other drugs, however, with the classic one being steroids. About 15% of people prescribed prednisone have a dose-dependent affective side effect. When the first case studies were published about the psychiatric effects of anabolic steroids there was a flurry of criminal defenses based on this. Later research showed that the people who were more prone to 'roid rage' where people who also had antisocial personality disorder.

The final issue you'll hear about is the idea of paradoxical intoxication, in which a person has an extreme reaction to a small quantity of a substance. Roy mentioned the cases of homicide or robbery after only two doses of an SSRI; this would be an example of proposed paradoxical intoxication defense. (Actually, the best example of paradoxical intoxication I've seen is the movie Final Analysis. It's also a good illustration of the kind of criminal defendants who propose defenses like this.)

So that's my input. Pass the Paxil and stand back!

Dinah:

What never fails to amaze me is not that people have side effects or adverse reactions to medications, but the great variety of responses people can have to the same medication. If 70% of people will have a given response to a medication (hmm, let's say dimunition or resolution of depressive symptoms if we want to look at the cheery side of things, or sexual dysfunction if we want to look at the gloomier), well what about the other 30% of folks? Why is it that some patients have a great clinical response and there is no down side? Some people seem to be more medication-sensitive in that they are more prone to side effects or need lower doses of medicines, but there isn't necessarily carry-through from one class of drugs to another. So, we all know that Lithium may cause weight gain, but I've seen patients on high doses of lithium for years that haven't gained any weight, and we all know that zyprexa may cause weight gain (note that I say "may" because it's just not a given), so why will the same patient might tolerate one of these with no problem, and start piling on the pounds when you switch to the other?

Roy's reference gives several explanations as to why SSRI's might induce violent behavior: switch to mania (perhaps with psychosis), akathesia, activation, emotional numbing. Clinically, the question of SSRI-induced suicidal/homicidal behavior has always been a tough one: these medications aren't prescribed to people who are trooping along Just Fine. Suicidality is a very common symptom of Depression and SSRI's are prescribed for depression; we're left wondering if the SSRI caused the suicidality, began working and lifted the patient to the point of being able to act on the thoughts, shifted the patient into a bipolar mixed state, or simply was ineffective in treating the depression and was incidental to the final act.

Given the vast range of odd side effects/adverse reactions that people get from medications, the studies linking suicidal ideas in children to SSRI's and the extreme nature of the cases discussed in the PlosJournal article, it's probably reasonable to say that a very small percentage of patients given SSRI's may become violent. Still a bit of a stretch for me, because there are also people who have no history of violence who unpredictably kill someone, and it becomes hard to look at the correlation to a medication when tens of millions of Americans take that medication (kind of like I eat Twinkies and I didn't kill anyone) and only a few of them unpredictably become violent.

And what does this mean clinically? I think I'm left to say something fairly flat, like: Not Much, So Far. I don't work with children, where I believe the implications are broader-- the black box warning on SSRI's regarding suicidality may be giving pediatricians a moment's pause before prescribing them, and the latest recommendations suggest that kids be seen fairly often for the first month of treatment: probably not a bad idea, though perhaps cumbersome given the shortage of child psychiatrists.

To date, I have not seen a previously nonviolent adult become violent on an SSRI. People still enter treatment asking for these medications, and many people find they effect life-altering changes for the better. Some people have no response at all. Some people feel much calmer, less irritable, and better able to cope with what life throws them. Some simply cease to be depressed and identify that the medication makes them feel like their old, pre-depressed self. Often, people have sexual side effects and are left to make a decision. If someone were to report violent ideas on the medication, as with any distressing side effect, I would discontinue it. For an out-patient practice, the decision to take or not to take medications is ultimately the patient's; I can discuss the possible risks and the possible benefits, I can make a recommendation based on studies I've read and patient responses I've witnessed, I can strongly encourage someone to take medications, and ultimately I suppose I could refuse to treat someone who I felt I couldn't help at all without medication, but the final decision is generally an issue of team work, and often the patient comes in predisposed: "I'm never taking meds" or "Prozac made my best friend better and I want some of that stuff."

The vignettes in this story are striking. To date, I've not felt a need to warn patients that they might become violent: these cases are the exception, not the rule, not anywhere close. If I hear enough of them, I'll start warning people, until then, I'll leave it to the ever-present media, and I'll keep a close eye on my patients.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Unnecessary Consultations

In When Day Care Calls, Part III, Dr. Flea is annoyed that a parent wants an orthopedic consult on the benign to-be-outgrown condition of metatarsus adductor (translation: one of the kid's legs turns funny), all because the Day Care Director suggests there is more to be done. Flea gives in and refers the patient, against his better judgement.

I'm left to wonder, why the distress?

Is Flea worried the orthopedic surgeon will think he's an idiot for referring?

Is Flea worried the orthopedic surgeon will find something he missed? (shame, lawsuits, you name it)

Is Flea worried about the needless waste of healthcare dollars? (He hates it when his patients go to the ER unnecessarily, hates it even more when the ER docs don't consult with him)

Is Flea worried about wasting the orthopod's time?

Is this an issue of control for Flea? Won't he look bad if the orthopedist says "You arrived just in time, it's so good you have that wonderful DayCare Director to look out for you!" Will he gloat when the orthopod says "The pediatrician is right, they're nothing to worry about and little darling will outgrow this soon; never ever listen to those Day Care directors!"

Flea seems to be upset that the Day Care Director would second guess him, would suggest a medical consult despite his reassurances and her lack of medical training, and he may be insulted that the parent won't take his word on it for what is right.

It seems to be the nature of the beast that patients wonder if they're getting the best care. Doctors-bashing is fun, and we're bombarded by the media with images of physicians who've missed the diagnosis, who are lazy, money-hungry, egotistical and owned by the pharmaceutical industry.

Psychiatry has its own issues with referrals for consultation. Most psychotropic medications --especially anti-depressant and anti-anxiety medications-- are prescribed by primary care doctors, not psychiatrists. And primary care docs worry that they'll insult a patient if they say "You Need A Psychiatrist." Plus, in issues related to mental health, everyone is their own Day Care Director: often psychiatric symptoms are the same as what we might call Normal Reactions or You'd-feel-this-way-too-if-you-experienced-what-I've-experienced. Some patients resist the idea that their symptoms warrant getting help, they come for help at the insistence of a relative, a friend, the Day Care Director. Others long for a diagnosis, an explanation that absolves them of responsibility and that might even be something easily cured. Add to this the fact that psychiatric illnesses often include a symptom called Impaired Insight-- the inability to accurately see oneself (--"Damn it, I wouldn't be so irritable if you weren't such a Jerk!!!) and outside informants, Day Care Directors in assorted forms, can add invaluable information to the treatment process.

In a moment of empathy with Flea, however, I will say I prefer it when the Day Care Director says, "Maybe you should consult with a psychiatrist and see if there's a problem here," rather than, "You need to see a psychiatrist to get 900 mg of Lithium and 15 mg of Zyprexa for your Bipoloar Disorder."

Sunday, September 17, 2006

Today's Bloggy Quote

"Everyone seems to be be fleeing from the responsibilites that come from being who you are. I think that is why the blogsphere is thriving. It allows people to develop a fantasy self."

Mr. Siegel was suspended from The New Republic, where he's been a senior editor, for posting anonymous comments on his own blog. How do I get someone to pay me to write a blog???

Saturday, September 16, 2006

I hate House!

[posted by dinah]

There is a piece of my brain that is missing, I'm sure of it. It's the part that encodes names and facts about, and truly understands, Pop Culture. I think I had a little of it when I was a kid-- back then I could remember what artist sang what song, I could even remember their names, I watched the more popular TV shows (hey, if you check out the comments one of Dr. A's old posts, you'll see that I know all the lyrics to the Gilligan's Island theme song...so it was once intact), I knew who was in and who was out. Now, well, I recognize names, but I'm not so good at putting names and faces together. Whitney Houston, I was informed yesterday by a CNN BREAKING NEWS ALERT, has filed for divorce (for this they send me a special e-mail???) from her husband, some guy I never heard of. Is this something people care about and why don't I get a CNN alert for every celebrity divorce? Oh, the list of what I don't know is pretty long and I get some pretty strange looks from patients who are forced to explain a lot of things to me when I say "It's a familiar name..."

Okay, so some of my family members like this show House. The premise for the show, as discerned by the family member stuck with the option of either watching or relocating to another room in our house (that would be me) is as follows: There's this unshaven, utterly obnoxious doctor who is nasty to everyone from his co-workers to his patients and he has some problem with his leg-- until this season--which forces him to walk with a cane; just in case that's not enough, he pops narcotics throughout. He calls it like it is in the most unsavory of ways, a disenfranchised misanthrope, his saving grace, and the premise for the plot of each show is that he's an intelligent, unyielding diagnostician who refuses to settle for anything short of cure for his patients---when push comes to shove either he's devoted to them or devoted to his narcissistic need to be right in every show.

So if the medical puzzles were interesting, with some hint of realism, that might carry the show for me. Ah, last episode, we started with a psychotic kid with night terrors-- hallucinating and convinced that objects had been implanted in him by aliens-- gosh, the kid even gets one of the housestaff to believe in the aliens. House pieces together that his problem is the partial chimeric brain from a failed twinning process during the boy's invitro conception 10 years earlier. A psychiatric consult is never called -- I was dying to slip just a little anti-psychotic into the kid's ginger ale-- but by the end of the episode, Dr. House (he's either an infectious disease doc, or some super internist) is seen performing an open neurosurgical ablation of the brain tissue formed by the twin's DNA and the child can now live happily ever after.

Nothing about this protagonist is likeable, in fact, he's every patient's nonchalant, flippant, acerbic nightmare of a doctor. His only saving grace is his limp, it somehow makes him vulnerable, and that of course was cured serendipitously by the ketamine he was given intra-operatively during the final episode last season (who would have guessed ketamine could have such magical powers??) -- surgery of course was required to treat the gunshot wound he sustained at the hands of a disgruntled patient's husband : this fits in nicely with the current medical blog concern with violence to doctors. According to a DJ in Baltimore, the limp was cured because it was hurting the actor's back to walk that way, but he was back to both his cane and his vicodin by the second episode of the season.

My family loves this show, my friends love this show, my patients love this show. In my state of Pop Culture Brain Disorder (PCBD--what do I take for this, Roy?) I just don't get it.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

The Politics of Disease

In the late 1990's some watermen working on the Eastern Shore of Maryland came down with unusual psychiatric symptoms: sudden onset of disorientation, memory loss and inability to retain new information. The rapid emergence of these unusual cases was associated with an algae bloom which also killed off lots of fish. The organism that caused the problem, Pfiesteria piscicida, is an interesting little creature---officially known as a dinoflagellate (which to me sounds like a sexual disorder involving masochistic mastodons)---that goes through multiple different physical forms throughout its lifespan. It secretes a fat and water-soluble neurotoxin that affects humans if exposed in large quantities.

The toxic algae story garnered a lot of media attention and drew in marine biologists, medical researchers and neuropsychologists from Maryland, Virginia and the CDC. Some of the 22 original cases showed demonstrable severe memory deficits on testing that eventually resolved after about seven to ten days. The state of Virginia funded a team of researchers to conduct medical and psychological testing on affected individuals in that state and a special hotline was set up specifically to provide information to the public and to identify potential human exposures. Eventually a name was given to the disorder: possible estuary-associated syndrome (PEAS). Investigators established preliminary criteria to diagose the disorder:

- Symptoms develop within 2 weeks after confirmed exposure to estuarine water

- Memory loss or confusion associated with three or more associated symptoms persisting at least three weeks. The associated symptoms are: headache, skin rash at the site of water contact, sensation of burning skin, eye irritation, upper respiratory irritation, muscle cramps, and gastrointestinal symptoms

- No other identifiable cause for the symptoms

The algae bloom was attributed to nutrient run-off from shore-based businesses, specifically the large poultry farms that formed the basis of much of the Eastern Shore economy. Environmentalists rallied to the cause, and researchers found themselves caught up in the political cross-fire between environmentalists and the agribusiness industry. As one Pfiesteria expert stated:

"A problem is identified; scientists are asked by policy makers to present their best research on it; but then the policy makers disregard the science if it isn't politically expedient."

Now I come to the point of this post, which is the difficulty of discussing neutral, fact-laden evidence in a politically charged atmosphere. What got me thinking about this was the announcement from the National Institute of Health this week that there was no evidence to support the validity of a Gulf War Syndrome. I am expecting a fair amount of outrage from veteran's groups. I am concerned that politicians will bow to expedience and demand a new medical category where none exists. I have seen the PTSD diagnosis expand ad infinitum until the idea of a 'traumatic event' had no real limits.

The problem here, of course, is that human distress does not require a medical diagnosis to be valid. As Dinah pointed out in her last post "Behind Closed Doors" (conveniently relevant to my topic---we didn't plan this), we don't currently have a good schema for planning treatment for psychotherapy. If tens of millions of dollars are going to be spent to provide services to veterans, there must be a way of providing accountability and preventing abuse. The medical model is standard here. As the Pfiesteria story suggests, many people can believe they are diseased when in fact they are not. And giving someone a medical diagnosis can have huge implications so you better get it right. Dr. Fuller correctly suggested in her comment to Dinah's post that the medical model may not be relevant or applicable to psychotherapy, however it is presently the best---if not the only---form of accountability we have.

Behind Closed Doors

[posted by dinah and this may be part 4 in a multi-part series on psychotherapy, but i'm not exactly sure]

Let me begin by telling you about The Martian. This was a patient who was treated by ClinkShrink on the inpatient unit when we infant psychiatry residents together, and I assumed his care as an outpatient. He was a weird little guy who dressed like he'd popped out of another century. He was college-educated, worked, lived alone, didn't drive (this is notable in Baltimore, our mass transit system is awful), had no friends, had never dated (he was middle-aged), had never had sex, but he wanted to get married. How that might happen wasn't clear, but he did let me know that he would never have sex with a wife. The depression that had resulted in his hospitalization had responded well to medication; he came to see me for therapy and to continue the medication. Why The Martian? Ask Clink, she chose the nickname.

He came, he talked. I discussed him with my supervisor. The patient had a dream about the therapy. The supervisor said this was common early on. He said I was doing a good job. At some point, I forget why, he stopped coming, still unmarried, still a martian, but not depressed, and I'm not aware of any problems-- if I'm remembering correctly, he left pleased with his treatment.

Residents change supervisors every six months. My next supervisor was someone Fat Doctor might call Famous Psychiatrist (oh, we trained at a place where there are lots of Famous Psychiatrists, this one can be Very Famous Psychiatrist). I'm not Fat Doctor, so I'll just call him my supervisor. He heard about the case and wanted to know why the patient was coming. "So, he's coming to therapy because he wants to get married?" Well no, but probably that would be an okay goal by supervisor. I didn't know what to say. "Why are you letting this patient talk about his childhood?" Wow? I was a very new psychiatrist, I thought the patients were supposed to talk about their childhoods. Please don't tell my former supervisor, but years later, I still let patients talk about what they want in therapy, even if I do begin with a bit of role induction and some general directions, and even if I do sometimes point out that they might want to use the time a little differently. How come the last supervisor thought I was doing okay with this case? How come the patient hadn't seemed displeased or shocked by his care?

It's common knowledge that if you consult a surgeon, she'll recommend surgery-- well, mostly, it's kind of a joke, sort of not really, but you get the point. If you see an acupuncturist about your pain, you get acupuncture, if you see a physical therapist, you get physical therapy, and most internists/general practitioners/family practice docs would probably prescribe an antibiotic if you showed up with a fever, productive cough, and infiltrate on CXR.

And most psychiatrists will prescribe an anti-depressant, probably an SSRI--for a first time affair, if you show up complaining of depressed mood, anhedonia, sleep, appetite, libido changes, guilt and suicidal ideation. And most psychiatrists will prescribe an anti-psychotic agent if you're hearing voices or having delusional beliefs that the FBI is watching you through gadgets they've surgically implanted in you while you slept.

But what psychiatry doesn't have a consensus on is how long we see our patients for (oh somewhere between 5 and 55 minutes a session) or how often (somewhere between once a day and once a year) we see them, never mind whether we call what we do "psychotherapy" or how, exactly, we define and justify what it is we're working on during those psychotherapy sessions. Do we need to "justify" seeing patients for psychotherapy? Well, sort of: insurance companies want treatment plans, and as a society we spend a lot of money on psychotherapy...if it's your own funds it's one thing, but a significant portion of psychotherapy dollars come from insurance and government dollars. Even as psychotherapist who believes that therapy can be tremendously useful, I'm all in favor of thinking about why we're doing what we're doing and if it is effective and makes sense.

From a patient's point of view, especially the first time around (-- ah, mental illnesses are often either chronic or recurrent, there is a learn-as-you-go patient phenomena), the patient is someone who is suffering: a psychiatrist is recommended by a friend, a family doctor, an ER/inpatient unit, an insurance plan, and the patient goes. The very same patient could walk into ten different doors and be told he needs ten different things: anything from start this medicine, it takes a month to tell if it's going to work/ or more accurately to tell if it's not going to work: "come back then" to "you're a perfect candidate for psychoanalysis, five times a week and it will take years." Granted, even I don't think many psychoanalysts make such a recommendation on the first visit, but once or twice a week psychotherapy is often suggested. Or cognitive behavioral therapy with a more definative number of suggested sessions. Or, the patient is handed a prescription and told to see someone else for psychotherapy. In community mental health centers, where many people with chronic mental illnesses or limited resources, get their care, treatment is, if nothing else, a bit more uniform (I've worked at a bunch of clinics, in Baltimore, but also briefly in Louisiana during my Katrina stint, and it was the same there). Patients are seen by therapists (generally social workers), somewhere between once and twice a month, more often for some patients if the therapist and patient both have the time and interest, and the patient sees a psychiatrist-- monthly in some clinics, every 90 days in others if things are going smoothly. Still, I've seen new patients in a clinic-- depressed with some suicidal ideas, started them on a medication, and as I've walked out of the room, heard the therapist give them an appointment to return in a month and " go to the ER if you feel suicidal" (hmmm, I was thinking more along the lines of Come-Back-In-2 to 3-Days...).

I'm rambling (I'm prone to that), but my point is, despite practice guidelines, DSM-99R diagnostic guides, and lots of efforts to prove that what we do is useful, psychiatry continues to lack consensus about what it is we do, particularly with regard to psychotherapy, and we don't even have an adequate or consistant vocabulary to define what really happens when we sit alone in a room with a patient. I'll go on to say that while we might all agree on how to log what medications we prescribe (name, dose, route, number of pills, refills), we don't even have a consistant agreement about what it is we write in notes that go in the charts.

Okay, I'm off to do something.....

Monday, September 11, 2006

Thinking of Carlos

Is it okay to say that mostly I try not to think about the terribly sad things?

I had a group of friends in high school, some closer than others. I had not spoken to Carlos in many years. He was very smart, had a warm heart, and he and Steven nursed me through calculus and chemistry. I always suspected that he had a crush on our friend Igor (her real name is Diane, but somehow the nickname stuck). Mostly, I remember that he wasn't a stylish dresser, that he carried a brief case to class! When he went off to college at Rensselaer, I teased him "RPI where the men are many, the women are few, and the sheep are nervous." I remember talking to him on the phone once a few years later-- he had a girl friend, a woman he later married. I heard they had two little boys, but knew little else about how his life had gone.

Igor and I had been exchanging phone messages for some time-- nothing urgent, just to say hi.

After September 11th, there were a flurry of messages on our high school list-serve. Where was Sam? Sam chimed in, he was fine, he'd stayed home from work that day. Where was Carlos? Someone else chimed in that they thought Carlos worked for Port Authority on the New Jersey side, he was presumably fine.

I walked in the door a bit late that evening and my husband told me to call Igor right away. My heart sank, I dialed and simply said, "Carlos."

Carlos worked in the World Trade Center, he died in the disaster.

It was a horrible, anxious time, all the more so after I had a face--and a family-- to place on the tragedy. Please-- no sympathy comments for me-- Carlos was remote from my day-to-day life, and so many people lost loved ones who were integral to their lives. I just wanted to say that for so long after, I thought about him everyday, and I'm thinking about Carlos again today.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Arsenic and Old Reservoirs

From Baltimore Suburbs to a Secret CIA Prison

Apparently one of the CIA detainees being transferred from a secret prison to Gitmo is a former local boy. He is alleged to have planned to blow up underground gasoline storage facilities and to poison water reservoirs. There are a number of reservoirs here in Charm City. Tomorrow, on the fifth anniversary of 9/11, I will be busy feeling happy to be alive and unpoisoned along with my fellow ShrinkRappers. Before today I thought the closest I'd ever come to poisoning was to cook for myself.

Saturday, September 09, 2006

Roy: Stopping the scourge of P.E.

You all remember Physical Education class (Phys Ed) back in school, right? I recall that it was always looked upon with great anxiety.

I see they now have a drug that helps with P.E. It's about time.

I think it was the performance anxiety... where you truly measured up next to the guy (or girl, I guess... wife tells me it was the same for her) next to you to compete on strength and endurance. Who can go farther, further? Who went the longest? Could I hold out 'til the end?

It wasn't easy. Your coach, with stopwatch in hand, would yell "Go!". You'd start the race, and before you knew it, it was all over. Those days in the gym were the worst hours of high school. It was so embarrassing. The apologies. The disappointment. And I know I wasn't alone. In fact, the article says that up to a third of men had this problem.

Globe&Mail: “We tend to think of this as, ‘Oh, it affects novices, the first time, and young people,' ” Dr. Pryor said Thursday from Minneapolis. “But no. There are some people who have this who are older, and oftentimes it affects them their entire lives.”

I hadn't thought that P.E. had such a prolonged effect on folks. I guess there's a kind of P.E. P.T.S.D. And this medicine helps. This drug, dapoxetine by ALZA, helped guys' stamina "last three, four times what they were before."

Just think of how that can relieve the anxiety of whether you can hold out long enough to go the distance. In football, you'd be able to finally score a touchdown. In baseball, you'd be able to steal third base and slide into home. Playing golf, you'd finally master your stroke and get a hole in one. In basketball, this drug would help you shoot the furthest. And surely, in cricket, you could manage the most sticky wicket.

Of course, we do have to temper our enthusiasm until further studies demonstrate the effectiveness of dapoxetine. Too often, the press goes off half-cocked about the latest fad drug. Let's not be too premature. However, I've already bought stock in ALZA, because when the FDA ...

...um... what's that?

It is?

Oh. Well, that's very different.

Never mind.

Friday, September 08, 2006

Rabbits 1, Tigers 0

"You didn't need to calm her. She's an emergency room nurse. She's used to dealing with crisis."

Roy: CMHC Dream

It's 4:30 AM now, and I just awoke suddenly, heart pounding, frightened, unable to go back to sleep.

I just had a dream.

Kinda weird dream, but ending in one of those sit-bolt-upright-awake kind of deals. Might as well tell the story, since I can't go back to sleep.

So I'm sitting at my desk, leaning back in my chair, talking with a social worker about the "client" she just evaluated. We are sitting in a small front office room, big enough for two desks and a small waiting area. I mean small waiting area. There are 3 of those cheap, plastic-with-metal-legs type of chairs. The only light comes from two fluorescent, overhead fixtures, one missing it's lens, both with only half the bulbs working, in addition to that coming from the frosted, display-type, storefront windows on either side of our front door, which has a 2-inch, metal bell on it. The walls are old, cheap paneling, some with faded bits of yellow tape where signs used to hang. Two of the dropped ceiling tiles in a corner are stained with old water damage, the top of the paneling there buckling slightly. There's a few signs on the wall and a calendar... The kind that that comes from the local car dealer... turned to September, with a red 1965 convertible Impala on it.

It's the same calendar page I saw yesterday morning when I picked up the rental car at my car dealer while my 1999 Chevy Malibu was getting serviced (the sunroof won't close). I remember it because it looked a lot like my old 1964 convertible Chevy Malibu that I drove throughout college and medical school. My first car. That was a good car. It was never in the shop, and I had no trouble closing the roof.

Interesting. The paneling in the dream office was the same as in the car rental office, as were the waiting room chairs. Well, that's how dreams go. And I'm sure it's Dinah's mention of her writing class that has got me in this writing mood.

The door bell jingles and in walks a little girl. "Can I help you?" I ask.

"Do you make home visits?", she asks, in a surprisingly mature and succinct way.

"We can. What do you need help with?" I'm working in a small, community mental health clinic (CMHC), set up just off Main Street in a storefront office that probably used to be a bakery or something.

"My mom's needs help with her depression. I just live two blocks away." She turns and goes out the door, standing there, waiting patiently. This is just odd. She doesn't sound frightened or upset. I tell the social worker that since there are no scheduled patients for me, I'll go check it out. I grab my jacket and my ID badge and go outside, in the cool, fall air. The girl starts walking, and I follow her.

I see that the office is in a past-its-prime, small town. In fact, it is very much like the CMHC that Dinah and I used to work in, some 10 years ago. So I follow the little girl, blond hair, probably 6 or 7, dressed in a just-started-first-grade kinda dress. It's like 3 in the afternoon and sunny. She stays ahead of me, very determined and sure of herself. We walk silently. She's clearly on a mission.

We walk up to this block of small, one-floor houses, all with front porches and mature trees in the front. There's a metal, chain-link gate, but it's open. We walk up the three concrete steps, which are off-kilter from tree roots pushing them up. We go up the steps to the front porch and she takes out a key from her pocket and opens the door.

Now I'm expecting this place to be a mess. I have this image of a mother, laying in bed all day, with little Susie six-year-old taking care of the house. The little girl excuses herself while I stand awkwardly in the foyer. It's a nice, little home, not at all a mess. I hear some murmuring, then the little girl comes back and motions me to follow her. I take a deep breath and enter the small living room, where mother is sitting, dressed nicely, on a sofa chair. I'm thinking, "She doesn't look depressed. What is all this about?"

I introduce myself as a psychiatrist who works with the County Mental Health Department, and that her daughter came to us and asked for some help. As I'm talking, I notice that the woman makes no eye contact with me, instead staring at her daughter the whole time, with this odd fake smile and a look that seems to silently be saying to her daughter "what the hell did you do this for but I can't look upset about it or else something bad will happen."

As I'm talking, I become aware of a man dressed in a checkered, polyester suit, standing about three feet to my left, leaning against the wall, listening to me talk. I'm also vaguely aware of two other, younger children.

"So she told you I'm 53, did she?" he blurts out, more to himself than to me. I'm talking for another minute or two and I'm getting the vibe that father is getting upset, from the looks on the mother's face. The little girl just sits there, staring straight ahead, attentive but silent, as if she's waiting for things to fall into place.

All of a sudden, the father starts talking to me in a very calm, disarming voice, then suddenly changes his demeanor to intense anger and rage, precedes his action with a "Why, you little...", then leans in towards me and violently spits in my face.

Bold upright. Heart pounding. I'm awake in my living room, where I'd fallen asleep.

And I'm still trying to decide if it was a dream or do I need to do something. I quickly realize that it was a dream, but just can't get back to sleep. I think that I would have rushed out of the house, then called 911, charging the father with assault, followed by a call to Child Protective Services. The whole thing was just weird.

Might as well get up and make some coffee.

Thursday, September 07, 2006

When Reality Gets To Be Too Much

There is life beyond the blog.

There is life beyond the blog.

There is life beyond the blog.

Last month, I wrote about how The Blog was ruining my life. It was distracting me from writing, diverting my angst and motivation and I found myself reading other people's blogs, following Fat Doctor's life as if it were my own. A summer thing, I told myself, with the hope that with the end of summer I might enroll in a grad school course, might let Shrink Rap take its rightful place in my life as just a blog, not an obsession.

Tonight, I had my first class-- a grad school course on Fiction Techniques. It's been a long time since I took a college course. Back then, we didn't register by fax. We didn't email the professor before class began. We didn't print out the parking map from a pdf file (--oh, I didn't have a car, never mind a computer). And the professors never began class by commanding the students to Turn Off Your Cell Phones. Other than that, it was pretty much the same.

I don't think I was the oldest person in the class, but I might have been the second oldest. There were a few people who looked a little older than the rest of the crew, and I'm not very good at guessing ages. Many of the students were in their twenties, and there were some very interesting hair chemicals involved.

I have homework.

I need to go buy my text books--Amazon is definately an improvement from those days of old. And I have to write a 2 to 4 page paper where a fictional character discusses a difficult event in his/her life. My character is going to be a 54 year old. His difficult event is going to be slipping on the snowy steps and injuring his back-- a devestating injury resulting in chronic pain. He becomes disabled, angry, depressed, and addicted to pain medications. You may be asking Why? Isn't that like going to work, rather than writing fiction?

Maybe I'll change my mind when I go to actually write it.

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Tigers 1, Rabbits 0

In the natural world it's easy to tell the predators from the prey. The predators have claws, talons, sharp incisors and stereoscopic vision. The prey tend to breed like telemarketers and travel in packs. They use camouflage to look like inanimate objects or distasteful creatures. Humans have adapted some defensive techniques from the natural world in rather ingenious ways. During World War II (what is it with me and history, anyway?) maritime traders discovered that more of their cargo made it past German U-boats if they travelled in fleets or convoys rather than individually with armed escorts. My personal favorite adaptation was by a runner who painted large owl-like eyespots on the top of his cap to keep the starlings from dive-bombing him. (I wonder if if dive-bombing birds are a problem for rock climbers...er, boulderers. I guess you could throw ropes at them. If you used ropes.)

In the natural world it's easy to tell the predators from the prey. The predators have claws, talons, sharp incisors and stereoscopic vision. The prey tend to breed like telemarketers and travel in packs. They use camouflage to look like inanimate objects or distasteful creatures. Humans have adapted some defensive techniques from the natural world in rather ingenious ways. During World War II (what is it with me and history, anyway?) maritime traders discovered that more of their cargo made it past German U-boats if they travelled in fleets or convoys rather than individually with armed escorts. My personal favorite adaptation was by a runner who painted large owl-like eyespots on the top of his cap to keep the starlings from dive-bombing him. (I wonder if if dive-bombing birds are a problem for rock climbers...er, boulderers. I guess you could throw ropes at them. If you used ropes.)To bring this back to relevance, in the correctional world I have trouble telling the difference between predators and prey. There are times when it seems to me that a lot of the teardrop tattoos, gang symbols and gold teeth are mainly defensive adaptations to keep away the predators. I've also been told by some prisoners that they purposely cultivate a 'crazy' unpredictable persona to keep from being victimized. One correctional psychologist told me about an inmate who hated being touched so much that he purposely smeared feces over his body to keep the officers' hands off him when he came out of his cell (to shower, I hope). Meanwhile, I'm ironically working with my seriously mentally ill patients to try to help them 'blend in' to general population and seem as normal as possible.

The more concerning thing is predator recognition, both for personal safety (see previous blog post Risky Business) and for the safety of my patients. Sometimes inmates come for mental health care specifically because of victimization issues that they may or may not be willing to tell you about. They may tell a false or misleading chief complaint specifically to get moved off a tier or to get hospitalized away from the predator. Predators also have been known to 'scam' their way on to a unit specifically to get close to someone they're 'leaning' on. And you have no clue this is going on unless a tier officer knows his or her unit well enough to fill you in on the history. Repeated psychiatric hospitalizations are sometimes a clue that the tier has become an unfriendly place for prison-prey. It all boils down to experience, the ability to piece together knowledge about specific units and inmates, and familiarity with enough prison scenarios to read between the lines.

And now for something completely different. Well, not completely different. In fact, it's actually somewhat relevant for a change.

According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the average annual rate of non-fatal violent crime is 16.2 per 1,000 workers for physicians, 21.9 for nurses and 68.2 for mental health professionals. (And no, I don't know how they classified physicians who are mental health professionals.) OSHA identifies a number of risk factors for workplace violence in healthcare settings: the presence of forensic patients (that's my euphemism for OSHA's reference to 'criminal...acutely disturbed violent individuals'), increased numbers of mentally ill patients (yeah yeah even the Federal government blames those 'dangerous nut cases'...sheesh), but most importantly the presence of available drugs or money (back to the nature analogy---it's not good to resemble food). Remote or isolated workplaces with unrestricted pedestrian traffic are also a risk factor. OSHA provides a list of engineering controls (apparently their term of art for physical modifications) to prevent violence (see OSHA link). Personally I think there's no substitute for a large human presence with a soft voice and laid back temperament. And forget the personal alarms and buzzers---just scream.

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Risky Business

What you may not know is that Dr. Wayne Fenton, a schizophrenia researcher at the National Institutes of Mental Health, was killed this weekend by a schizophrenic patient he was seeing in his private office.

I didn't know Dr. Fenton, I don't think I even knew of him, but I learned of his death at a Labor Day barbeque I hosted, from one of my neighbors who is also a schizophrenia researcher and who did know him.

My husband asked me last night, "Don't you worry about being alone in your office with patients?" I don't. There's only so much I can worry about, and for the most part, my patients constitute a rather tame crew. My husband says that when he lets himself think about it, he does worry about me.

Even if I don't wrestle with crocs for a living, the reality remains that people with psychosis can behave in unpredictable ways. As a child, I lived across the street from a neurologist. His office was across the hall from a psychiatrist and one day, a patient walked in and shot and killed the psychiatrist. Needless to say, my mother thought I should consider another career.

I once briefly treated a patient who was preoccupied with thoughts of killing his former psychiatrist and who had previously been banished from a local psychiatric institution for threatening psychiatrists there. He was psychotic, bizarre, violent, and needy. After a few months, I sought consultation and, as a result of this, told the patient I would not continue to see him in my office-- the consultant had suggested that it was too intimate and secluded a setting-- but that I would be happy to see him at the clinic where I work. The hours I'm at that clinic conflict with the hours this patient worked, so while I made the offer, I knew it wouldn't fly. When I told the patient, he became angry and began pacing around my office and making threatening gestures. I went into the hallway, and to get him to leave, I had to have the police come. He phoned later and wished me a doomed future-- perhaps the closest anyone has ever come to the "F*** Off Rule" SHP talks about in her post today. Foofoo added to SHP's comments with a horrifying story of how he'd been assaulted, bitten, and broken by a violent patient he'd pulled off an intern. I'm impressed by his bravery, saddened for both of them at the violation. I'm not so sure I could have gone on working -- at least not in that setting-- in the face of such horrors.

I didn't know Dr. Fenton-- this story isn't really mine to tell but from the perspective of a fellow psychiatrist who is left to wonder a bit about issues of safety, and to feel badly for my neighbor who is distraught. My heart goes out to Dr. Fenton's family and friends, and somehow this all feels a bit closer to home than the other stories I've heard this weekend.

Dr. Fenton remembered across the blogs

Saturday, September 02, 2006

Roy: Human Brain Evolution

In Science this week is an article by Popesko, et al., reporting on an interesting genetic finding, where a particular gene sequence is duplicated in humans more than in primates, and suggests that the duplication may have something to do with being human. Macaque monkeys have 4 copies of the gene, MGC8902, whereas the more advanced chimpanzees have 10, and humans boast 49. The gene itself contains multiple copies of the domain known as DUF1220.

"In addition to labeling in the cerebellum, neuron-specific DUF1220 signals were present in the cortical layers of the hippocampus. DUF1220 domains were also abundantly expressed in neurons within the neocortex (frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes), thought to be critical to higher cognitive functions."These researchers have previously done genome-wide scanning across species to locate another 133 genes which may have been responsible for our leap from the trees to the living room sofa (okay, so perhaps Tom's sofa antics can be explained by being a few genes shy...cursed Thetans).

The above linked page has a link to an article about yet another mind-expanding gene, MYH16, which is different in humans versus the nonhuman primates. The human version is missing 2 tiny nucleotides, resulting in smaller jaw muscles. With smaller jaw muscles, we need less skullbone for it to attach to, resulting in more room for brain expansion. Researchers have dubbed this mutation RFT, which means 'room for thought'.

It's just so far out that a handful of genes could be responsible for homo sapiens, while a number of labs are trying to add these genes to other animals -- perhaps there is a Cornelius in our future yet.

[I'd love to see what NeuroCritic has to say about this area. If you haven't checked out his site, it is an always thought-provoking, information-rich blog that is one of Blogspot's must-RSS sites.]

Other blog perspectives:

Cognitive Labs

John Hawks' Anthropology

Slashdot ...interesting discussion thread here

Modalogica ...expands on the Planet of the Apes theme (also see Slashdot discussion)

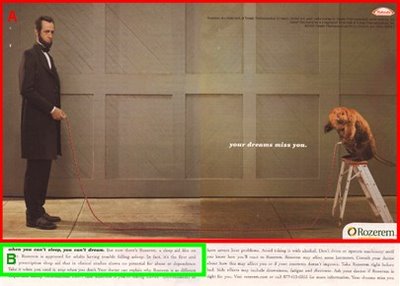

Sweet Dreams?

So I was reading Real Simple, a magazine that a neighbor brought over because she thought I'd like the recipe it had for lemonade, and I came across this ad for Rozerem:

Huh? Rozerem is a sleep medication that claims not to have an addictive potential. I've even prescribed it a few times. But what does Abraham Lincoln have to do with it? And why is he playing jump rope with an otter?

I googled "Rozerem Abe Lincoln" and discovered that it's part of an ad campaign for the medication: Abe and a talking beaver.

But why?

If you want to read more, try John Mack's Pharm Marketing Blog. He doesn't get it either.

ShrinkRap Magical Mystery Tour

So begins the ShrinkRap Magical Mystery Tour. So far all the ShrinkRappers have denied any connection with Roy's disappearance, but who really knows? Floorboards remain untouched and Max isn't talking. Was it Sargeant Pepper in the billiard room with a candlestick? Dinah (she says not) in the gym (ha! she hates exercise) with a giblet? Stay tuned to the blog for more clues.

Friday, September 01, 2006

Under The Floorboards: The Case Of The Missing Co-Blogger

Let's take a quick look at the facts here.

We have three psychiatrist co-bloggers and what do we know:

dinah is a mini-van sports mom (albeit a reluctant Snack Parent) who owns a personable dog with limited wants. She does psychotherapy in a solo private practice, works in a hospital-based community mental health center, and loves hot fudge sundaes. She will ride a segway at the request of a friend, but so far has not gone for Wall Climbing.

ClinkShrink works in a prison, used to own cats (who are mysteriously now dead by means not related to their gifted giblets), has a fascination with serial sex murders, is a walking encyclopedia of criminal history and torture, invited a man named FooFoo whom she's never met to vacation with her at a Russian Prison Camp, and looks like a nun (her self description, furthered by the fact that she doesn't do hair chemicals). If that's not enough, she posts links to costumes for guinea pigs (this just isn't normal, folks).

Roy is a smart computer geek who loves the ironic side of pop culture, works under a pile of disorganized papers, and fancies himself a victim of ADHD (prodded along by his wife who really just wants him to pick up his dirty socks--or so that's the story I've written) and self-medicates with Sudafed. He's an overworked shrink in an understaffed department trying to eek out a living.

Roy disappears.

Why, I want to know, does everyone want to look under MY floor boards.

" What has dinah done with Roy?"

I've seen it more than once, I've even seen it on someone else's blog.

I guarantee, if you dig up my floor boards, you'll find moldy chicken nuggets and apple sauce (no added sugar). If you dig up Clink's floor boards: who knows.

I am, I contend, innocent until proven guilty, and perplexed as to why I'd even be considered a suspect.